[The following is extracted from Niklas Schrape’s “Gaia’s Game”, found in Afterlives of Systems]

There exists a curious tension between Latour’s reading of the Gaia hypothesis and Lovelock’s own wording that makes one wonder if they are actually writing about the same thing. This disparity might be explained by the development of cybernetic thought itself: Lovelock developed his original hypothesis under the influence of what has been called first-order cybernetics. He doesn’t refer to the concept of recursion by von Foerster or the one of autopoiesis by Maturana & Varela – and neither does Latour. But as Bruce Clark points out, the Gaia hypothesis does indeed incorporate concepts of second-order cybernetics:

Simply put, first-order cybernetics is about control; second-order cybernetics is about autonomy. (…) Unlike a thermostat, Gaia – the biosphere or system of all ecosystems – sets its own temperature by controlling it. (…) In second-order parlance, Gaia has the operational autonomy of a self-referential system. Second-order cybernetics is aimed in particular, at this characteristic of natural systems where circular recursion constitutes the system in the first place. (…) natural systems – both biotic (living) and metabolic (super organic, psychic, or social) – are now described as at once environmentally open (in the non equilibrium thermodynamic sense) and operationally (or organisationally) closed, in that their dynamics are autonomous, that is, self-maintained and selfcontrolled.

According to Clark, Margulis, influenced by Varela, overcame the metaphor of the thermostat in her latter works and focussed on the autopoietic qualities of Gaia. From this perspective, Gaia is not primarily a system of feedback-loops that can be described, analysed, controlled, and maybe even build; it is an ever evolving and becoming entity that emerges out of a co-evolutionary interplay between life and non-living matter. This autopoietic concept of Gaia is quite similar to Latour’s understanding of an animated, evolving assemblage. Moreover, in this view of Gaia, the structure and components of the earth system are not given, they emerge out of geohistorical events and contingent trajectories. Latour emphasises this point when he interprets Lovelock’s reasoning about the influence of early bacteria on the composition of the atmosphere:

If we now live in an oxygen-dominated atmosphere, it is not because there is a preordained feedback loop. It is because organisms that have turned this deadly poison into a formidable accelerator of their metabolisms have spread. Oxygen is not there simply as part of the environment but as the extended consequence of an event continued to this day by the proliferation of organisms.

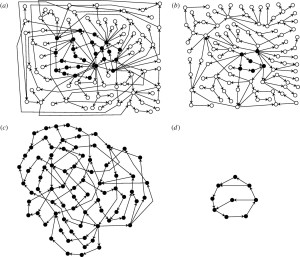

Latour’s reading of the role of oxygen in evolution makes it apparent how insufficient Lovelock’s Daisyworld model is in regard to his understanding of Gaia: The feedback-loops of Daisyworld are products of an engineer, they exemplify a mechanism, they do not emerge out of contingent and changing conditions. Therefore, Daisyworld cannot surprise: only a few possible pathways can be realised during repeated runs of the simulation. To take up a notion from computer game theory: the possibility space of Daisyworld is very limited.

But Daisyworld fits to Lovelock’s view on cybernetics. After all, he is an inventor, who always liked to engineer his own research instruments. He describes feedback-loops and mechanisms – and who does so might fantasise about controlling them. And indeed, Lovelock does write about the possibilities for geoengineering, and even co-authored a book about the terraforming of Mars. Thus, Lovelock’s original first-order Gaia hypothesis must be differentiated from a second-order Gaia hypothesis, developed in the latter works of authors like Margulis. While first-order Gaia can be observed from the outside to some degree (Lovelock repeatedly refers to the view from space), is a unified system, and might partially allow controlling its feedback-loops, second-order Gaia is a emergent property.

If first-oder Gaia is the product of a cybernetic engineer and found its incarnation in the computer-model of Daisyworld, the question arises how second-order Gaia might manifest in silico. This question is not just pure speculation as the concept of Gaia revealed itself to be bound to specific technological conditions: If the cybernetic thermostat is the original model for Gaia, and if the Daisyworld model follows the system dynamics approach, what would be a second-order equivalent?

In fairness to Lovelock, he has made some modifications to his thesis since 1983. The original conception was indeed dominated by the notion of homeostasis but that is not true of versions in the last 25 years. Latour is quite clear that his is a loose and, to use his word, ‘charitable’ reading. That said, putting Margulis’ version into conversation with Lovelock’s would be very interesting. Quite necessary in fact. Great post, though!

Reblogged this on Social Network Unionism.